Fiberglass for First Plastic Sports Car Developed in Connecticut 65 Years Ago

Naugatuck, CT – Bill Tritt and his company Glasspar were growing in the fiberglass boat business by leaps and bounds, and while the bulk of their business was always boats and ships, in late 1949 he had started working with Ken Brooks to produce a fiberglass sports car body. By early 1950, Bill was looking to expand and take on new business, and in that year Tritt brought on investors that would allow his company to grow.

Things were looking good for Glasspar, and Tritt wanted to add sports car bodies to Glasspar’s product list, but there was a problem. Lots of companies needed supplies, but none more so than the U.S. government. The summer of 1950, when Glasspar began its expansion plans, was also the same time that the Korean War started (Korean forces invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950), and this war continued through the summer of 1953.

Resources were in scant supply, and everyone wanted what was available. It was in that setting that Tritt pressed forward to find more supplies – polyester resin and fiberglass mat – in Southern California. At every corner he turned, supplies were being dedicated to the war effort. Glasspar’s dreams of expanding were suddenly in a precarious position.

In 2000, Daniel Spurr interviewed Bill Tritt about this very moment in time for his book Heart of Glass, a terrific story on the birth of the fiberglass industry in postwar America and how it revolutionized the boat industry. Here’s what Tritt had to say:

“At this critical point in Glasspar’s growth, the story becomes one of great serendipity and plain luck. The Korean War dealt us a near mortal blow. We suddenly were unable to obtain polyester resin because it was all going to aircraft and other military products. Our purchasing history was laughable, as was I in my fruitless search for suppliers.”

“Then, strictly by chance, I saw a notice of the opening of a new chemical company in a warehouse in South Los Angeles. I had never heard of the company, Naugatuck Chemical, although it turned out to be a division of U.S. Rubber. I didn’t know what the warehouse was to house, but with nothing building in the shop, on a nice day, I borrowed the Boxer from Ken Brooks and drove to the warehouse.”

“It was large and appeared empty, but I went inside and found a little office. In the office was a personable young man named Bud Crawford, who informed me that the warehouse primarily handled shipments of polyester resin from Connecticut, headed then to the big boys.”

“He was most sympathetic to our problems, but he had no way to divert any of the resin without an order from the War Department. We concluded there was no way I could get even a drum of our lifeblood’s chemical equivalent from Naugatuck. We walked out to the loading dock to bid farewell and, when Crawford saw the Boxer, he asked, “Hey, what’s that?”

“Less than twenty-four hours later, Earl Ebers, head of Naugatuck, a chemist and devoted proponent of Fiberglass Reinforced Plastic, arrived in California, came to the (Glasspar) plant, and committed Naugatuck Chemical to sending us an immediate (air freight) supply of resin (trade name Vibrin).”

This historic moment was captured by more than one person. Back in 1951, Bert McNomee was in the operations area of the public relations department for Naugatuck Chemical. From 1968 to 1976, Bert was the director of public relations for U.S. Rubber, but during 1951, he was at ground zero of what was about to happen with Glasspar and fiberglass sports cars.

Bert reviewed his memory of these early years back in Shark Quarterly, a magazine about Corvette history, in the summer of 1997. Here’s what Bert had to share:

“In 1950, Bill Tritt had designed and Glasspar built a custom body to update a friend’s wife’s jeep chassis (note: see previous story on Glasspar for correct reference to a 1940s Willys). This work caught the attention of our West Coast man, Bud Crawford, and he told Mr. Ebers about it. When he heard about Tritt’s work he decided we would go out there.”

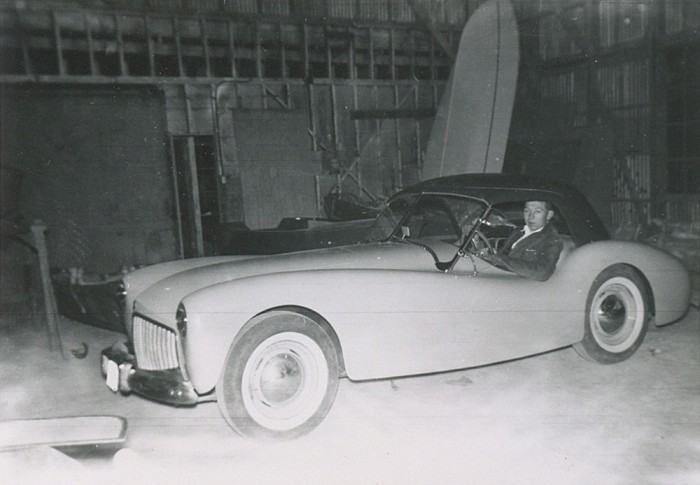

“We arrived on a Saturday and, I remember, checked into a little known place called the Mayfair Hotel. Then on Monday, Bill Tritt took us out to Costa Mesa to see this car. I thought, “Holy Mackerel look at this car!” It looked like an early Jaguar. They asked me if I wanted to take a ride in it. I surely did. So off we went. It was amazing; it cornered well, and with the light body it was peppy.”

“Mr. Ebers asked me, “So Bert, what do you think?” I said that I thought we had a chance to get it into LIFE Magazine, like he wanted. But first we need some good pictures of the car. Now a lot of things happened pretty much at the same time. My job was to get busy on the press coverage.”

“For my part, I hired Tom King of the Blackstar Association, locally, to take some pictures. These were just the preliminary photos so I could get some interest going at LIFE Magazine. When we got back to New York, I called Bill Payne of the “new products” section at LIFE and showed him these preliminary photos.”

“Bill was also a car buff so he was quite interested in the idea of a fiberglass car for his section. We met for lunch with Earl Ebers and talked about how the car body could be presented to make a really interesting story.”

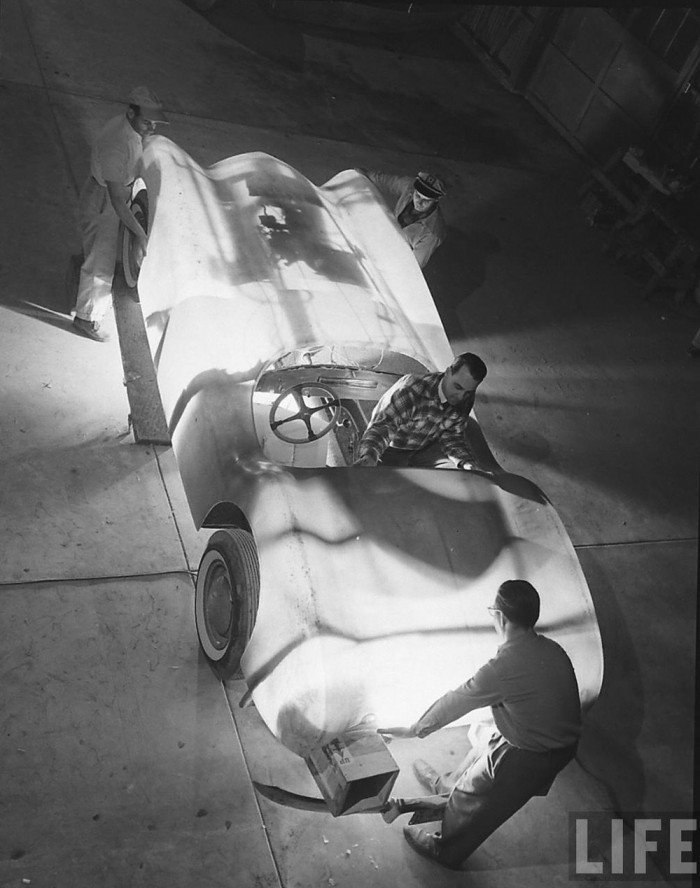

“We had to make it clear, pictorially; that this was a car body that was different from any other car body you had ever seen. I told him that before the car was painted, the body was actually translucent. That did it. It lit up all kinds of ideas in Bill’s mind. He started talking about how we could lower the body over the car and light it from underneath. The ideas came together and he sold the story to his editors.”

At this time, Earl Ebers went up to Naugatuck to meet with George Vila, who was the General Sales Manager, and John Coe, who was the Vice President. They both agreed that Naugatuck Chemical would subsidize the construction of four prototype cars, which was the amount Tritt wanted to justify setting up the bucks and molds.

They also agreed to send Earle out to Costa Mesa to work on the first four models and to oversee the operation. And so Glasspar and Naugatuck were joined at the hip in terms or making fiberglass sports cars a reality, and no small job was laid out in front of them to make this dream a reality. In fact, in just a few short months Bill Tritt would have to:

- update the plaster buck so a new mold could be produced (changes in the grill design occurred at this step)

- create a new mold that could stand the rigors of production

- debut the Brooks Boxer at the Petersen Motorama in November 1951

- and finish at least one full sports car that Naugatuck had paid for, preferably by the end of 1951

Bill Tritt commented in Heart of Glass about the meeting in late summer as follows:

“We had unbelievable credit and an order for a car to show at Philadelphia Plastics Exhibit in (March) 1952. Life magazine was set to do a feature story; one hundred eighty degrees from a few days before.”

In the fall of 1951, the team from Naugatuck Chemical returned with Life Magazine photographer J. R. Eyerman. During this time, they photographed the Brooks Boxer in action shots for the magazine, captured Bill Tritt working on the plaster buck for the G2 sports car, showed the steps in making a fiberglass body, and more.

In fact, in photographing the sports car body being built, they would be capturing the very first body being built from the production molds. This would become the second Glasspar sports car built – the Alembic I.

In preparation for today’s story, I called Bert McNomee (he’s doing great and has been a constant source of support and information for the history of these times), and asked him about how the name Alembic I came to be for the second sports car built by Glasspar.

Bert reminded me that Naugatuck Chemical was a chemical company first, and in chemistry, Alembic has its origin in equipment involved in the distillation process. According to Merriam-Webster, the definition of Alembic is either an apparatus used in distillation or something that refines or transmutes as if by distillation.

And so, with great excitement, enthusiasm, and the backing of a large company, the second Glasspar sports car was born, the Alembic I. Bill Tritt, Glasspar, and Naugatuck Chemical pressed forth, and to the delight of all, Life Magazine published the article in February 1952 and the world of fiberglass sports cars was never the same.

Article Courtesy Hemming’s Daily

Geoff Hacker is a Tampa, Florida-based automotive historian who specializes in tracking down bizarre, off-beat, and undocumented automobiles. His favorites are Fifties American fiberglass-bodied cars, and he shares his research into those cars at ForgottenFiberglass.com.

Glasspar Cars are featured on Ray Evernham’s Americarna episode “Forgotten Fiberglass” on VelocityTV; Check your local listings for date and time.